Book Review 1421: The Year China Discovered the World

In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue...

...but Columbus wasn’t the only one who sailed to the East away from the sun,

The Son of Heaven sailed that way too...

...in 1421.

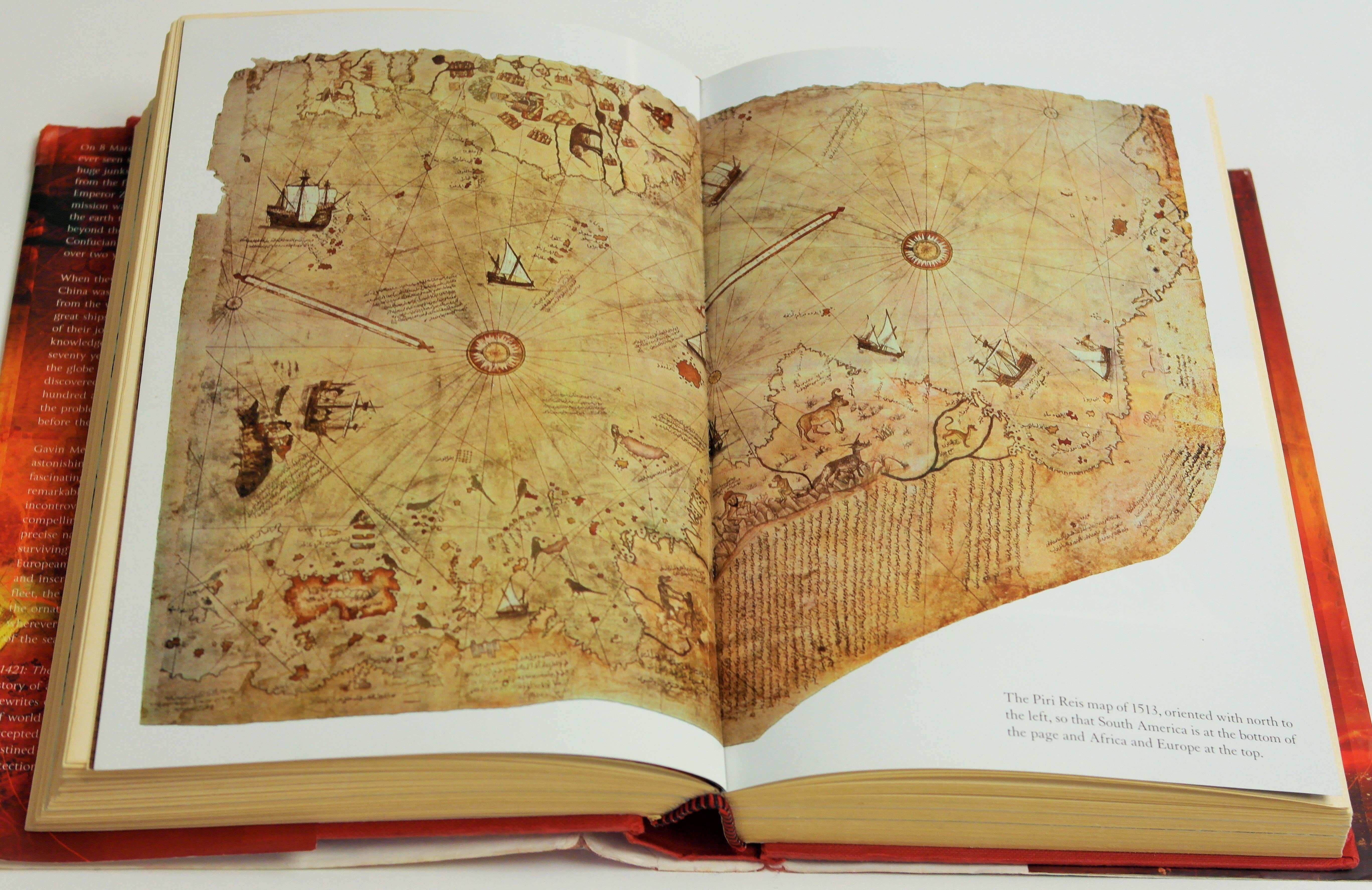

In the early 1990s, former British Naval Officer and Commander of HMS Rorqual Gavin Menzies came across a map in the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota which aroused his curiosity. Signed and dated 1424 in the name of Venetian cartographer Zuane Pizzigano, the map illustrates the coastlines of Europe and Africa with surprising accuracy for that period. Particularly, clearly displayed on the map are four islands in the Western Atlantic Ocean bearing the names Satanazes, Antilia, Saya and Ymana. Upon comparison with modern maps, Menzies was unable to locate any islands at that longitude. Could Antilia possibly be the leeward island of Puerto Rico and Satanazes represent the windward island of Guadeloupe in the Caribbean Antilles? Furthermore, how could a nautical chart produced in 1424 identify islands which, according to conventional history, were first discovered by Columbus on his four voyages between 1492 and 1500? How can the discovered have been identified before the discoverer had even been born? In his book *1421: The Year China Discovered the World** Gavin Menzies answers these questions and offers life-altering insights into modern world history.

-Cover illustration 1421: The Year China Discovered The World (Bantam Press, edition 2013)

Menzies alleges that in 1421, four vast fleets of at least 800 Chinese junks, over 500 ft in length, set sail from China in a voyage of exploration and imperialisation. Led by Admiral Zheng He (郑和) and his four captains—Zhou Wen (周闻), Zhou Man (周满), Yang Qing (杨庆) and Hong Bao (洪保) —these explorers successfully charted The Americas, the Arctic Polar Region, the Antarctic and the region of Australasia. Controversially, Menzies declares that before his first expedition in 1492, Columbus had access to, was in possession of and forged nautical charts created by the Chinese upon their voyage.

Menzies elaborates on the triumphs of the Emperor Zhu Di (朱棣) also referred to as ‘The Son of Heaven’ and the Yongle Emperor (永乐帝) who was the 3rd Emperor of the Ming Dynasty (明朝 1368-1644) and reigned over the Yongle Empire from 1402-1424. Having defeated the Mongols in 1387 and amalgamated the northern territories of Mongolia into the Yongle Empire, Emperor Zhu Di organised for large sections of the city Ta-tu—originally designed and built by the Mongol Leader Kublai Khan—to be demolished and the city was remodernised, adopting the name Beijing (北京) or ‘The Forbidden City’ (紫禁城). Upon completion of this fourteen-year modernisation project, the city was inaugurated with a lavish event. Statesmen from all territories who paid tribute to the Ming Empire, including dignitaries from Malacca (modern Malaysia), Bengal, the Maldives, African Nations, India, Arabia and Asia, were called to Beijing to offer compliments to the Emperor. As a reward, the dignitaries accompanied Admiral Zheng He and his armada receiving protection on their homeward journey.

As a naval expert, a great deal of Menzies’s claim is founded upon nautical evidence. Having joined the British Royal Navy in 1953, Menzies served on HMS Newfoundland on a voyage from Singapore to Africa around the Cape of Good Hope and then north to the Cape Verde Islands docking finally in the UK. This voyage mirrors with significant accuracy part of one of the voyages discussed in the book 1421. Menzies uses expertise of sailing winds gained during this expedition, to analyse historical charts to substantiate his claim. In particular, this journey would have made use of the southeast trade winds which Menzies suggests propelled the Chinese fleets northwards along the western Coast of Africa. He substantiates this claim with pictorial references depicting unidentified stone carvings found on the Cape Verde Islands. Also, a shipwreck supposedly containing artefacts from the early Ming era and a picture of the remains of a road of flat stones submerged in The Bahamas also appear in the book. Popular theory attributes this construct as a remnant of the ‘lost city of Atlantis’, although Menzies suggests it was built to assist the Chinese sailors haul their gigantic vessels (the size of modern super-cruisers) onto land for repair.

-Piri Reis map of 1513, illustration in 1421 The Year China Discovered The World (Bantam Press, edition 2013)

As shipbuilders, the Chinese possessed an engineering savvy in excess of contemporary Europeans which Menzies suggests facilitated this momentous journey. They also had knowledge of astronomy which allowed them to develop an accurate measurement of latitude in the Northern Hemisphere by following the star Polaris. To achieve a measurement of longitude, Ming astronomers built 25-foot-square observation platforms for the measurement of the movement of the moon’s shadow during an eclipse. Menzies suggests relics of such platforms are located along the East Coast of America and Australasia and offers diagrams to illustrate their shape and size. Measurements taken using these observation platforms in conjunction with sophisticated methods of determining time enabled Admiral Zheng He and his fleet to create accurate charts of the territories they discovered, leading the Pizzigano chart cartographer to develop the map which encouraged Menzies to research this subject.

Conversely, Menzies provides DNA evidence indicating many Chinese voyagers settled in North and South America as well as Australia. He also cites Aboriginal and Native American Indian folklore dating from this period, and particularly cultural peculiarities noticed around the Strait of Magellan. The prominence of traditional Chinese methods of varnishing and decorating trinket and storage boxes as well as techniques for grinding grain which have been assimilated into the culture in this region suggests the Chinese sailed through the straight before Magellan, and successfully colonised this region. Additionally, the presence of types of Asiatic chickens and local names for plants serve as further reinforcement.

-A replica of Zheng He’s treasure ship in Nanjing’s Baochuan Shipyard (Copyright: Xinhua)

Well researched and backed up with historical facts, pictures and images to substantial his claim, Menzies does write out of a personal interest in the topic. His book 1421 is primarily a narrative explaining Menzies’s own voyage of discovery revealing historical assertions which, when presented together, display a thought-provoking alternative view of history. In fact, it cremates the conventional world history purported in history books. Equally as important to note is Menzies’s professional background: As a formal British Naval Admiral, he has the expertise and personal experience necessary to corroborate that it would have been possible for a fleet of Chinese junks, the size of modern day super-cruisers, to follow nautical currents and winds which continue to propel sailors across the globe today. The evidence he presents based on the Chinese superior techniques of measuring latitude support that the Chinese would have been able to chart their progress along the journey. This then reinforces that it was possible for fifteenth-century cartographers to copy nautical maps produced by Chinese sailors during this journey.

Nevertheless, Menzies has been heavily criticized within the academic community for this alternative and controversial record of history. It does bare consequences for international relations and begs the questions: Why has this history remained silent for so long? How has the conventional theory that Columbus discovered the Americas become the dominant history? Similarly, 1421 is not an academic text and the evidence is not presented in a clear manner to suggest the type of writing expected of an academic. The novel does present a great deal of evidence to suggest that the Chinese discovered the New World before Columbus and the Europeans. However, this unconventional view is yet unaccepted throughout the academic community and is not widely corroborated.

**First published in 2002, Bantam Press, a division of Transworld Publishers, London, (2nd Bantam edition, 2003). Also published in 2003 under the title: 1421: The Year China Discovered America. HarperCollins Publishers, New York (editions 2003, 2004, 2008).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn