Autumn in China: The Beauty of the Seasonal Changes

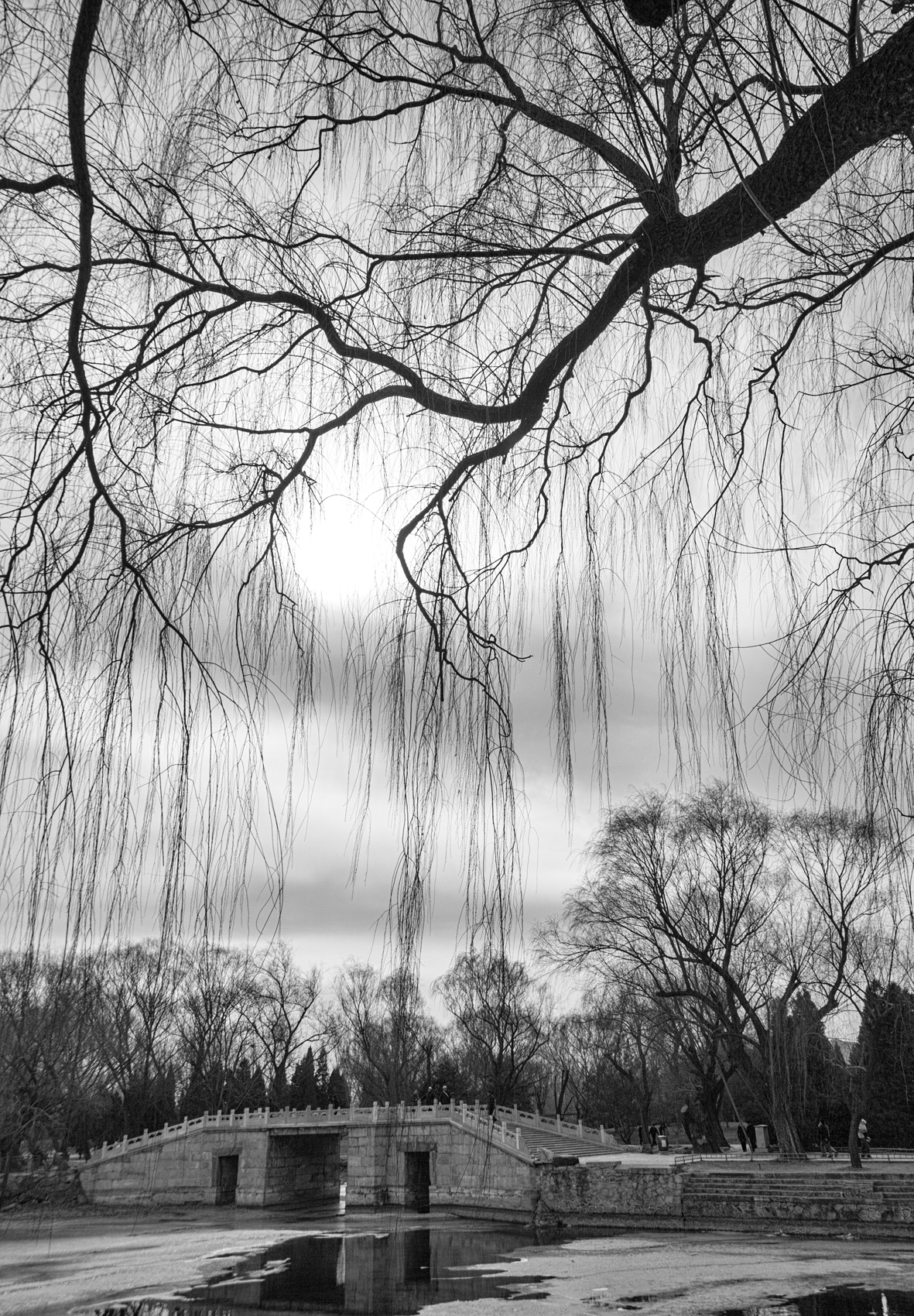

WHEN AUTUMN COMES, the fresh colours fade away, the sun lowers and the whole atmosphere changes to a more pensive mood. The autumn makes us think about decline, loss of strength, and impermanence.

Ancient Chinese poets were very sensitive to the change of seasons and many poems about autumn are preserved. The following poem was written by Ma Zhiyuan (马致远 1250-1321), a poet of the Yuan dynasty (元朝 1271-1368):

Kū téng lăo shù hūn yā,

枯 藤 老 树 昏 鸦,

Withered vines, old trees, a faint crow,

Xiăo qiáo liú shuĭ rén jiā.

小 桥 流 水 人 家。

A small bridge over flowing water, some houses,

Gŭ dào xī fēng shòu mă,

古 道 西 风 瘦 马,

An ancient path under a westerly gale, a meagre horse,

Xī yáng xī xià,

夕 阳 西 下,

The evening sun is declining.

Duàn cháng rén zài tiān yá.

断 肠 人 在 天 涯。

The heartbroken tramper is yearning for his home.

As is characteristic of Chinese poetry, the poet speaks directly to us. His melancholy mood is in line with the changes in nature. Flux, decline and old age are all suggested in a few words. The season has changed, so too have nature and the living creatures. The yearly seasonal change, in which the summer gradually loses its grandeur within an innumerable variety of individual processes making up nature, has been described with great beauty. The changes in intensity of the sunlight and the accompanying decrease of temperature affect the various kinds of living societies through a large number of influences. The overwhelmingly complex transitions of decay leading to new forms of order take place on cosmic scales of magnitude.

These processes of change have been expressed in classical Chinese philosophy, perhaps in greatest depth in the Neo- Confucian thinking developed by Zhu Xi (朱熹 1130-1200). He found his metaphysical inspiration in The Book of Change (《易经》 Yìjīng). The ‘myriad things’ in our universe create themselves through qi (气), the quality that is ‘within shapes’, providing them with actuality. Qi has been translated as vital force and is part of a duality. The other part is li (理), ‘above shapes’ prior to qi, and serving as the principle of permanence amid flux and bringing multiplicity into unity. Both principles can be viewed as the dipolar character of the Great Ultimate Tai Chi (太极), the foremost principle of unity and wholeness. Becoming and process originate from the interplay of li and qi. They can be appreciated in terms of the two modes yin (阴) and yang (阳). In turn, they interact with the five phases: metal (金 jīn), wood (木 mù), water (水 shuĭ), fire (火 huǒ) and earth (土 tŭ), thereby giving birth to the ‘myriad things’.

A second Chinese poem, called Autumn Air (秋风词 Qiūfēng Cí), was written by Li Bai (李白 701-762), perhaps the greatest poet of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝 618-907):

Qiū fēng qīng,

秋 风 清,

The autumn air is clear,

Qiū yuè míng,

秋 月 明,

The autumn moon is bright,

Luò yè jù huán sàn,

落 叶 聚 还 散,

Fallen leaves gather and scatter,

Hán yā qī fù jīng.

寒 鸦 栖 复 惊。

The jackdaw perches and starts anew.

Xiāng sī xiāng jiàn zhī hé rì?

相 思 相 见 知 何 日?

We think of each other, when do we meet again?

Cĭ shí cĭ yè nán wéi qíng!

此 时 此 夜 难 为 情!

My feelings are hard, this hour, this night!

The two poems here are focused on the most frequently experienced aspects of autumn, but the Chinese poets also recognise that each season of the year has its own specific beauty. Let me therefore finish with a famous poem, called Mountain Travel (山行 Shānxíng), written by Du Mu (杜牧 803- 852), a poet of the late Tang Dynasty:

Yuăn shàng hán shān shí jìng xiá,

远 上 寒 山 石 径 斜,

Far away on the cold mountain a stone path leads upwards,

Bái yún shēng chù yǒu rén jiā.

白 云 生 处 有 人 家。

Among the white clouds is a village where people have their homes.

Tíng chē zuò ài fēng lín wăn,

停 车 坐 爱 枫 林 晚,

.Stopping my carriage, I admire the maple wood during the fall of the evening,

Shuāng yè hóng yú èr yuè huā.

霜 叶 红 于 二 月 花。

The frosted leaves are even more red than the flowers in early spring.

While travelling in the cold autumn mountains, the poet is overwhelmed by the autumn colours of the maple forest, and this experience leads him to stop his carriage to enjoy this sight with his whole heart. The beauty of nature has not changed in the 1200 years that passed after Du Mu wrote this poem.

The early Chinese poets experienced the world with acute and sensitive perceptions of the world’s essential qualities, which led to expression of thoughtful insights in poetical language that still evokes deep meaning.

All photos by Du Yongle(杜永乐).

I am grateful to Dong Jiajia (董佳嘉) for putting the Chinese characters into the text.

By Jan B.F.N. Engberts

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn