A Dutch Artist's Mission to Clean China's Smog: Interview with Daan Roosegaarde

Dutch artist and innovator Daan Roosegaarde (1979), is the founder of Studio Roosegaarde, the social design lab with a team of designers and engineers based in the Netherlands and Shanghai. Now Roosegaarde and his team are developing a safe, energy friendly installation to capture smog and create clean air in Beijing and they are also working in China on other intricate designs, such as Smart Highways which are roads that are more sustainable and interactive because of the use of interactive lights, smart energy and road signs that adapt to specific traffic situations. Daan Roosegaarde has gained international recognition with his social designs, connecting the world of imagination with innovation.

Liu: Nowadays, one of the top keywords about China is smog. When I googled Studio Roosegaarde, I saw the remarkable project name, Smog Project. And many Chinese people know you are the Dutchman who has the mission to clean the smog of Beijing. That is very impressive. How did you get yourself so much associated with smog?

Roosegaarde: We have had some cooperation with China from the day we started the first studio which was based in the Netherlands, but quite soon we started the second studio in Shanghai. What we always appreciate and like a lot is, on the one hand, we are working on a design for the future, to think about what is coming; and on the other hand, we have the great desire to use technology to get there. And when we showed our project DUNE in Hong Kong and mainland China, people were very enthusiastic about it. DUNE is a public interactive landscape that interacts with human behaviour. This hybrid of nature and technology is composed of large amounts of fibres that brighten in response to the sounds and motion of passing visitors. Chinese people are very open to that. So we did a lot of exhibitions and public art works in China. But one day I was looking out of the window from my room in Beijing and on Monday I could see the city around me, but on Tuesday and Wednesday I couldn't see it anymore because of the problem of smog. And I was thinking maybe we should design and create a solution to fix that problem.

Liu: Great thinking! I read that the mayor of the Beijing city is really supportive of the Smog Project. Did you initiate the communication with the city?

Roosegaarde: Yes, the project itself was self-commissioned by our studio. We teamed up with some experts in the Netherlands, but also in China, who are specialists in smog because we needed to work together to create the cleanest park in Beijing as part of the Smog Project itself. You must also have seen the smog rings, the jewellery that is made out of actual smog. We suck up the smog particles and compress it and make it into a diamond. So when you donate or buy the ring, you give about 1000 cubic metres of clean air to the city. And we think Beijing, as the capital and as one of the most serious smog afflicted cities, is a good place to start to give something to the people. And it has been great to work together with Beijing, not only with the government, but also with the artists from the Beijing Dashanzi Art District (also known as the 798 Art District), to actually make this happen.

Liu: So how did the procedure go with you approaching the mayor of the Beijing city; did it take you a long time to get the support from the government?

Roosegaarde: We met the Vice Mayor for the first time during the last Beijing Design Week in October. And four weeks ago, I met with the President of China in the Dutch palace in Amsterdam during his state visit to the Netherlands. We had eight minutes with him and his wife, and we signed a MoU (Memorandum of Understanding), a sort of letter of intent, with Dutch Minister Bussemaker of Education, Culture and Science and China’s Ministry of Culture to make sure the project actually happens. It is going to be a co-creation, and of course, it’s very important that the government supports the project and that they are open to it. We are working together with the creative industry to make sure it actually gets realised.

Liu: You mentioned the agreement signed by the Dutch minister. What is the significance to your studio? What does this agreement mean for your studio?

Roosegaarde: We think it’s an important project to create incentive, to create a project for the future of the city, the future of a ‘smart city’, which is good for the people, good for industry and good for the economy. And we do it by making it very tactile, by building it. We know how to do it. We have the technology. We have an idea how to realise it. But of course it should always be a collaboration with the local government, to work together, to choose the park: Where should we do it? When should we do it? What's the story? How can we make sure that people understand the right message? The smog-free park is not the solution, but an incentive to work together to make a whole city smog-free, for instance by cycling more. So it’s very important to get recognition and support from the official level, especially in China where government is very important. When the government is supportive, people will accept it as a valid and important project. That is why creating common understanding and getting official support is part of the design process for me. It’s great to learn and to exchange ideas. It’s a lot of fun and I told them that I was inspired by their smog. That was a funny joke, of course. But they understood that. And we have also met with the President and the Dean of Qinghua University. They are very interested in promoting high-tech innovation, promoting this kind of science and making the city better again. So we are not saying that we know everything. Absolutely not. I am trying to say: let’s work together to make the city even better. We cannot do that alone.

Liu: Sure, that is a great point. I also noticed in your CV you have a long list of awards. Among them is China’s Most Successful Design Award. Which project brought you this award? Is it the smog project?

Roosegaarde: I think it was for the oeuvre, so for the whole series of projects that we’ve done. There are twelve projects we are working on right now. And one of those projects is the Smart Highway project about interactive and sustainable roads.

Liu: You have the Shanghai studios, with projects like the Smart Highway and also the smog project. How do you like the business environment in China so far?

Roosegaarde: You know, it is different from Europe, for sure. I think in Europe, there is a tendency to spend a lot of money, time and energy on Research and Development, on the idea. And then we spend ten to twelve months working on an idea before we can realise all the details. In China, things go much, much faster. Which means, sometimes you just start, you launch and learn, and then you go back and you update. I am not saying it is better or worse, but there is a different rhythm at play. You have to accept that and you have to make an art of the profit. While for me the most important thing is quality; quality of how people experience the quality of materials; that you make something that works, and it remains working. So I love the brightness, the speed of China, and the scale: very fast, very big. But at the same time, I sometimes try to slow it down a bit in order to make sure it has the quality that I have in my brain. That is sort of a creative process, a creative struggle. And I think that is very cool.

Liu: Based on your past experiences, how do you define the opportunities in China?

Roosegaarde: There are great opportunities in China. In Europe, they take a lot of time for Research and Development. But sometimes Europe is too slow. You have to find the balance between the fast and the slow. So that’s what I love about China: that there is this incredible desire for the future, especially in my generation, like 30 to 35-year-olds. It’s a new generation of Chinese people who are becoming bosses of their companies. And they have been abroad, they have been to London, they know the world a bit. And they are very, very open to new ideas. They invite me to their homes to eat and to hang out and to learn. And I think that’s incredibly fun to make new friends and, based on that, start to realise new projects. But it takes some time to get to know each other, and to build up trust because the stuff we do is also very radical. It’s radical innovation. And we are not optimising an old system. We are saying: no, we should reset and make something completely new, because the old things don’t work anymore. I think the new generation in China is ready for that, absolutely.

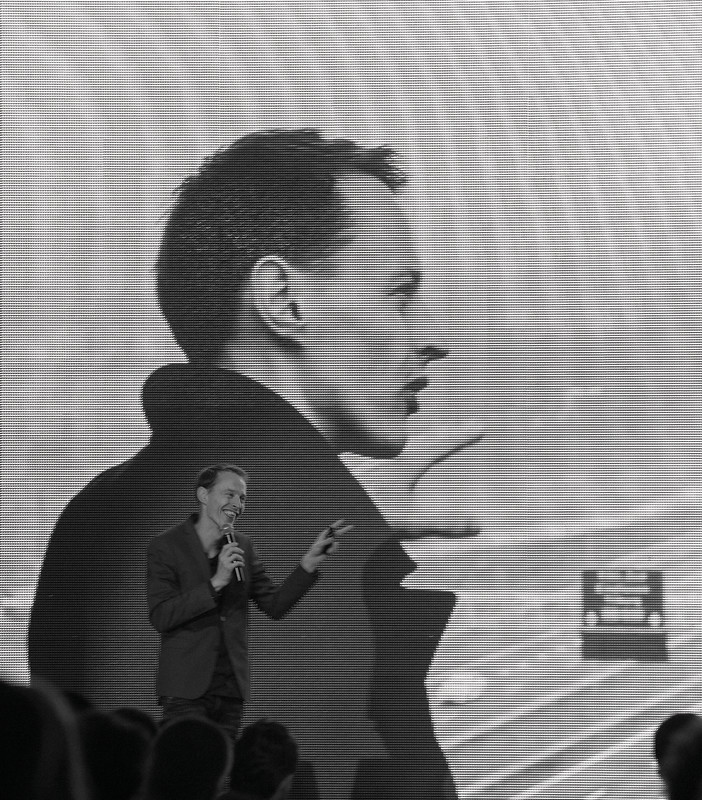

Liu: You have given lectures in many universities in China. How do you like the experience?

Roosegaarde: University students in China are very eager, incredibly eager. They ask a lot of questions and they do their homework quite well and they are familiar with all the projects. They are also very interested in the process, like how do you go from idea to realisation. I think I as a Dutchman, as a westerner, I have really been trained to always ask why. Why is it like this? I always question things. Maybe in the beginning, Chinese people are sort of shy. When I say something, they always say: “Yes, it’s okay, because you are the tutor, we believe you.” And I say: “No, no, you have to be critical yourself! Maybe I am wrong, I don’t know, let’s have an open conversation.” What I want is not me telling them what to do, but I want a dialogue. I want an interaction. In the beginning, Chinese students are not really used to that, but if you give them a chance to learn, they learn really, really fast.

Liu: I know you just had a trip to China in March accompanying the delegation with the Dutch minister Bussemaker of Education, Culture and Science. Do you have any new observations on China and new ideas from this trip?

Roosegaarde: I am getting to know it much, much better. I have been travelling in China for the past four or five years intensively. But right now we are building these things, so it is important to have a group of people who believe in you and to choose the right client who is really interested in the concept, the story, not just in it for the money, but also believes in the project. So I will go there in five or six weeks to talk about the first production of the smog rings, and to meet some Chinese manufacturers, to make it happen. You know, it is a city with so much potential, and so many great challenges. And I think, it forces us to be creative to survive.

Liu: I heard about your impressive lecture on the future of the world. What is your anticipation about the future of China?

Roosegaarde: Well, I think it’s very clear that we cannot keep on going like this. We cannot keep on growing and growing, you know, it will eat everything up. So in a weird way, we should not do less, but we should do more, and maybe invest more in creativity, in new ideas and new innovation to deal with the challenges and poetry of today’s China. So, we should think about an energy-neutral city which is based on good energy or about making parks where people can enjoy the weather and just enjoy themselves. That is, I think, as important as economic progress. So, this balance between commerce and creativity is important. And I think if China does that, there is a bright future. If it ignores it, you might hit a big concrete wall. But I think China has conquered many, many challenges before, so I am sure a new balance will be established. And I think China’s new president is really good at finding that balance.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on Twitter

Share on Twitter Share on LinkedIn

Share on LinkedIn